Towards the end of our working season, when the mornings get dark and nippy, the Woodpeckers can be found surrounding the wood stove (coffees in hand). Us tree nerds love to muse over each interesting log before we throw it on the fire. For the newer recruits, it becomes an impromptu lesson on tree biology based on the findings of “the Father of Modern Arboriculture” Alex Shigo. We thought it would be fun to share our “woodshed wonders” and unpack how they came to be, with the help of our friend Shigo.

Kevin Anderson, owner of Woodpecker Tree Care, was given one of his first lessons in Shigo’s teachings from instructor and researcher Tracey Mackenzie. Tracey is an assistant professor in the Department of Plant, Food, and Environmental Sciences at Dalhousie, and encouraged Kevin to examine his woodshed for valuable lessons on the inner workings of trees.

Our first “Woodshed Wonder” comes from Kevin Anderson’s pile: a poplar with telltale signs of an old injury.

But how do we know that this poplar was injured? It’s with the help of our trusty guide, Alex Shigo.

Shigo’s signature phrase was “touch trees,” which is a philosophy that guided many of his arboricultural findings. With the invention of the one-person chainsaw in the 1950s, Shigo was able to dissect trees longitudinally and examine how they grow, function, and change throughout their years. Much of what he uncovered contradicted what he had learned in university, and it changed the way arborists think about trees forever.

One of the important concepts he shared pertains to this particular log. In reference to tree injury, he said “When you hit a living thing, it reacts. When YOU hit a tree, it does something. When a tree is threatened, it doesn’t just stand there. It establishes boundaries.” That is something that human beings share with trees, but it is important to note a major difference between what happens when we are injured versus when a tree is injured. Trees don’t heal. So what happens when a tree is injured?

To answer that question, we have to follow Shigo’s example and get up close and personal with the tree. This log was conveniently split for home heating and can give us a clear view of the inner workings of this poplar.

As you can see, there is a noticeable bump in the wood, along with darker, oval-shaped wood where the wound is. What we can see here is how trees prevent themselves from becoming infected with micro-organisms and decaying, which is a big contributor to tree failure. Shigo realized that wood responds to injury with chemical and physical changes to prevent decay, which he could see during his dissections. He named this phenomenon Compartmentalization of Decay in Trees (CODIT), which is exactly what happened with this poplar.

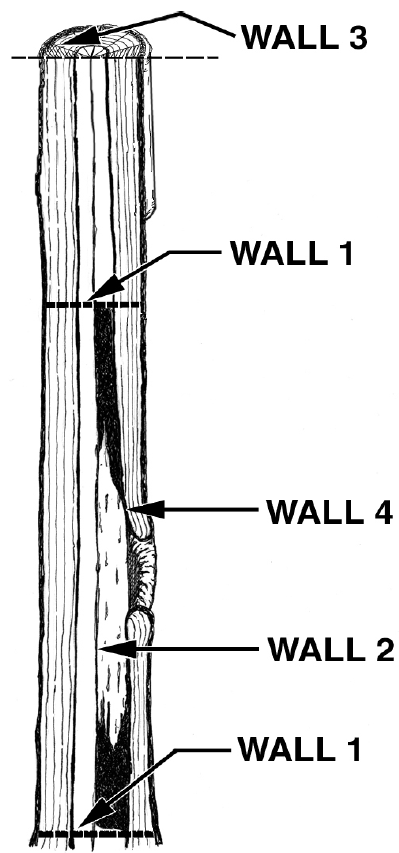

Instead of healing a cut or scrape with new cells as humans do, trees form “walls” around it (or make changes to pre-existing internal structures and systems) to prevent decay micro-organisms from spreading throughout the organism. There are four types of walls that trees create when they suffer an injury (or another threat).

WALL 1: This wall blocks the tree’s vascular tissue around the wound. This tissue transports fluid and nutrients vertically, so the horizontal wall prevents spread in that direction.

WALL 2: This wall prevents the radial spread of decay.

WALL 3: These walls are perpendicular to the stem. They can resemble a maze, and can sometimes change chemically and become toxic to any sneaky microorganisms that get in.

WALL 4: This is the “oval” wood we can see in Kevin’s photos and video. This is the strongest wall, called the barrier zone. It is woody tissue that grows on the outside of the tree and seals the wound. While it is chemically the strongest, it is physically weak.

What we are witnessing is the poplar compartmentalizing itself with walls to prevent decay. Not every tree will compartmentalize the same way, and there is still plenty to learn about the inner workings of trees. We do know, however, that the wound on this poplar is a pruning cut, a cut us Woodpeckers perform on nearly every job. A pruning cut is done specifically to encourage compartmentalization and prevent decay. A good pruning cut means a healthier tree!

Find any woodshed wonders in your stockpile this winter? Send a photo and we may dissect them for you, Shigo-style!